ETX Module: Use of EU ETS Revenues

While the EU ETS’s central goal is to reduce emissions, it has a co-benefit of generating significant revenues through the auctioning of EUAs, despite the fact that most allowances to industry are handed out for free. These revenues are a huge opportunity to finance climate action and support people through the climate transition.

Between 2013 and 2020, the EU ETS raised €68 billion in revenues for the member states, and this amount is increasing rapidly due to rising carbon prices, even as the cap decreases. In 2020, revenues amounted to €19 billion , and in the first half of 2021 alone they reached nearly €14 billion.

However, ETS revenues could have been much higher if it were not for free allocations to industry and airlines. It is estimated that between 2013 and 2019, €54 billion in revenues were foregone in this manner.

Source: WWF (2021), ‘Fit for 2030: optimising EU ETS revenues for people and climate‘

Currently the member states decide on how to use most of the revenues from the EU ETS as long as these uses are consistent with the loose guidelines contained in the EU ETS Directive.

Specifically, 50% of the revenues ‘should’ be used for so-called climate and energy-related purposes. This ‘should’ is a non-binding recommendation, and member states are free to ignore it, though they do have to report on their revenue use. By their own reckoning, national governments exceeded these requirements. The European Commission reports that member states spent approximately 75% of all EU ETS revenues on ‘climate action’ throughout Phase 3 (2013-2020). Only a small proportion of all revenues were spent on international action (3%).

However, WWF reports that seven member states did not, in reality, comply with this recommendation over the 2013-2019 period. Croatia, Italy, Slovakia, and Romania even spent under 20% of their auctioning revenues on climate action.

Although the ETS Directive lists spending areas which can be considered ‘climate and energy-related purposes’, this list is vague and rife with loopholes. Spending on these areas does not necessarily reduce emissions, strengthen resilience to the impact of climate change, or promote the transition to a climate-neutral EU.

Member state reports to the Commission show that the majority of revenues labelled as climate spending supposedly go to promoting renewables and energy efficiency. However, this is questionable because the reporting is vague and of very low quality, with some countries leaving most or everything of the reporting template empty. This does not allow for independent review of whether or not each euro reported as climate spending actually was spent on climate action. For example, some spending clearly goes against the ethos of climate action (and may even hamper the accomplishment of climate goals). WWF highlights how Germany and Belgium spent 7% and 9% of their revenues on subsidy schemes compensating industry for indirect costs, while Poland and Hungary spent €11.6 and €25.2 million of their respective ETS revenues to fund fossil fuel heating systems.

In addition, it is impossible to ascertain whether the spending earmarked for climate purposes was additional spending or whether member states labelled already committed funds as using ETS revenues to fulfill the ‘should use 50%’ recommendation. Ideally, all ETS revenues should be spent on additional climate action, and when revenues increase so should that spending. But in the absence of transparent earmarking of EU ETS revenues, this question is challenging to answer. Moreover, in a number of cases member states select climate parts of their national budget and label them as using ETS revenues even though there is no direct link. Three member states, for example, reported more spending as ‘use of ETS revenues’ than they actually had revenues in the first place: Slovenia reported climate spending representing 227% of its ETS revenues, Cyprus 220% and Lithuania 161%.

Revenues would be better spent if they were transparently earmarked towards specific climate projects, and could be significantly raised by abolishing free allocation of EUAs.

Established in 2017, the EU ETS Innovation Fund is an EU level fund dedicated to supporting the demonstration of innovative low-carbon technologies. The projects financed by the Innovation Fund are required to be innovative and at advanced technology readiness levels so that the fund can help them reach the market. These projects are meant for energy-intensive industries (including ones substituting carbon-intensive products), carbon capture and utilisation (CCU) and carbon capture and storage (CCS), innovative renewable energy and energy storage technologies.

The Innovation Fund has two pillars: large-scale and small-scale projects. Small-scale projects are defined as those with eligible costs under €7.5 million which can benefit from simplified arrangements for application, selection and definition of relevant costs. Large-scale projects are selected based on a two-stage application procedure. The ultimate responsibility for the selection of the projects that are awarded the grants lies with the European Commission. The Commission consults member states on the list of pre-selected projects before grants are awarded.

Projects are selected based on a set of criteria, the main one being effectiveness in avoiding greenhouse gas emissions compared to an already existing technology. The other criteria in order of priority are: degree of innovation, project maturity, scalability and cost efficiency.

The Innovation Fund supports up to 60% of the additional capital and operational costs of large-scale projects and up to 60% of only the capital costs of small-scale projects. The funding for each project is disbursed in the form of grants and up to 40% of the grants can be given based on predefined milestones before the whole project is fully up and running.

The first call for large-scale projects was launched in July 2020, with a budget of €1 billion, for breakthrough technologies for renewable energy, energy-intensive industries, energy storage, and carbon capture, use and storage. It received 311 applications for innovative clean tech projects. The results of this first call were published in November 2021. Seven projects were selected to receive funding. The successful projects cover different technologies, spanning from hydrogen production to its application in steelmaking and chemical production processes, renewable energy production and carbon capture and storage in the cement sector. The projects are located in Sweden, Finland, Belgium, Italy, Spain and France.

The revenues for the Innovation Fund come from the auctioning of 450 million EUAs between 2020 and 2030, as well as any unspent funds coming from the New Entrants Reserve (NER300), a programme with 300 million allowances allocated to it for the deployment of innovative, renewable energy technologies and carbon capture and storage. The total budget of the Innovation Fund, therefore, depends on the carbon price at which ETS allowances allocated to the fund are auctioned. At an EUA price of €50, it is worth approximately €22.5 billion. The draft European Commission Fit for 55 revision proposes to add an additional 50 million allowances on top of what is listed above.

The Modernisation Fund supports 10 lower-income member states for modernising their energy sectors and improving energy efficiency. In that sense, it is a solidarity mechanism under the EU ETS. It is split up among these member states, with each member state having an allotted share that can be spent in that country. It will be operational for the entire Phase 4 (2021-2030).

Member states select projects that they would like to fund under the Modernisation Fund, and send this list to the European Investment Bank (EIB), European Commission and a committee comprising the EIB, Commission and member states (the Investment Committee). Projects are either ‘priority investments’ or ‘non-priority investments’ – this status is decided upon by the EIB. Priority investments are in areas including, renewable energy, energy efficiency (if not related to energy generation using solid fossil fuels), energy storage, energy networks (grids, pipelines and district heating) and just transition in regions which are economically dependent on fossil fuels.

Priority investments can go ahead immediately, with the funds being subtracted from what was allocated to the member state the investment will take place in. Non-priority investments are assessed by the EIB on whether they are in line with the EU’s and the Paris Agreement climate targets, and, if they pass that test, are voted upon by the Investment Committee. Only 70% of the cost of non-priority projects can be covered by the Modernisation Fund.

At least 70% of all funds for each member state have to go to priority investments, which can be fully financed by the Modernisation Fund.

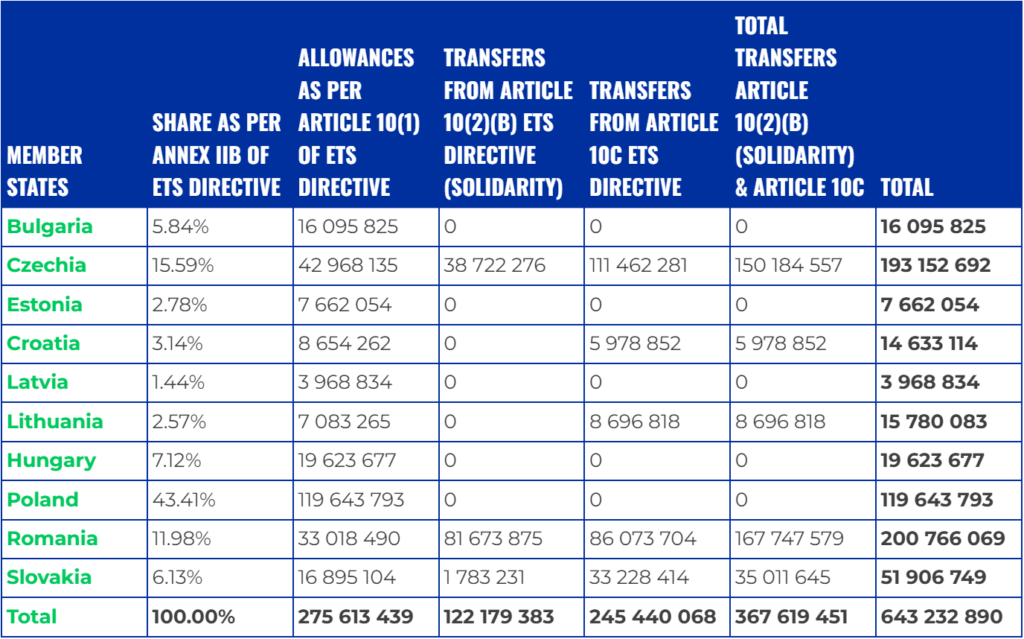

The Modernisation Fund is funded from two distinct sources, first revenues from 2% of the total allowances for Phase 4 are earmarked for the Modernisation Fund – this amounts to ca. 275 million allowances. Second, the beneficiary member states can allocate additional allowances to the Modernisation Fund from other sources – this amounts to ca. 365 million allowances. These do not go to the general pot, but instead are added to what that specific beneficiary has a right to. In total the revenues from auctioning more than 640 million allowances will end up in the Modernisation Fund (representing 35 billion euros at an EUA price of 55 euros). The shares allocated to the different beneficiaries vary substantially, with Czechia and Romania each accounting for nearly a third of the total fund (mainly due to them adding more than 150 million allowances from other sources to their shares), while Latvia can only count on 0,6% of the Modernisation Fund.