Trilogue triangulation: Mapping the positions of the EU institutions on carbon market reform

As the EU institutions enter into a three-way trilogue on the reform of the Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), we present you with this handy comparative analysis of the options on the table and Carbon Market Watch’s recommendations.

Almost a year after the publication of the European Commission’s proposal for the revision of the EU’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) as part of its July 2021 ‘Fit for 55’ package, the European Parliament and the Environment Council adopted their respective positions on the reform in June 2022. There are issues on which the Parliament and Council agree with the Commission, and areas where the three institutions diverge.

To find common ground and hammer out a common position on the EU ETS, the three institutions will, starting in October, engage in a so-called ‘trilogue’, a process in which they discuss and negotiate the ultimate details of the overhaul.

What is on the table for the trilogue? How do the positions of the EU institutions compare?

Comparative analysis

Higher ambition, lower emissions

The aim of the EU ETS is to reduce emissions in a cost-effective and efficient manner. The current related directive sets a 40% target of emissions reduction to be achieved by 2030.

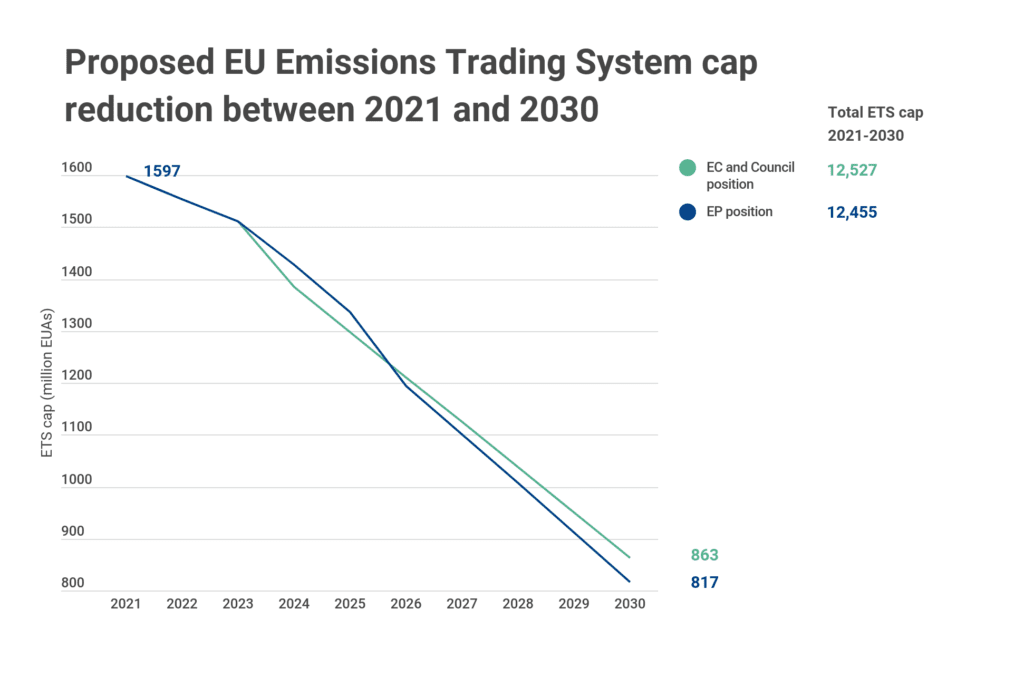

The launch of the European Green Deal raised the European Union’s climate ambition and required the revision of all climate-related policies, including the EU carbon market. The blueprint for this reform process came in the shape of the so-called Fit for 55 package, which aims to achieve a 55% reduction in overall EU greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. To do that, the European Commission proposed a 61% target for the highly polluting EU ETS sectors, in light of their disproportionately high emissions.

The Environment Council backed the Commission without changing any element surrounding the ambition of the EU ETS.

In contrast, the European Parliament, after months of negotiations and power struggles, managed to put its weight behind a moderately higher target. Through a faster reduction in the number of available pollution permits, the European Parliament agreed on a roughly 64% reduction in emissions for the ETS sectors by 2030.

None of the three options being considered by the EU institutions put Europe on a path that is compatible with its commitments under the Paris Agreement and with keeping the global temperature rise below 1.5°C.

In light of what the science says is required and the recent droughts and flooding, it is paramount that highly polluting sectors, such as those covered by the EU ETS, be made to slash their emissions and to speed up the transition to cleaner and more efficient production processes.

Extending the era of freebies

Free allowances are a form of protection against the risk of carbon leakage that has been in place since the beginning of the EU ETS.

However, by muting the carbon price signal for companies, these free pollution permits have also acted as a disincentive for emissions reductions, in particular when it comes to large polluting companies.

To incentivise deeper emissions reductions and reduce the risk of carbon leakage, the European Commission proposed the introduction of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). This mechanism would price the emissions embedded in imported goods consumed in the EU. It would also (progressively) replace free allowances to EU industries, thereby exposing EU companies to the full carbon price signal and incentivising investments in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

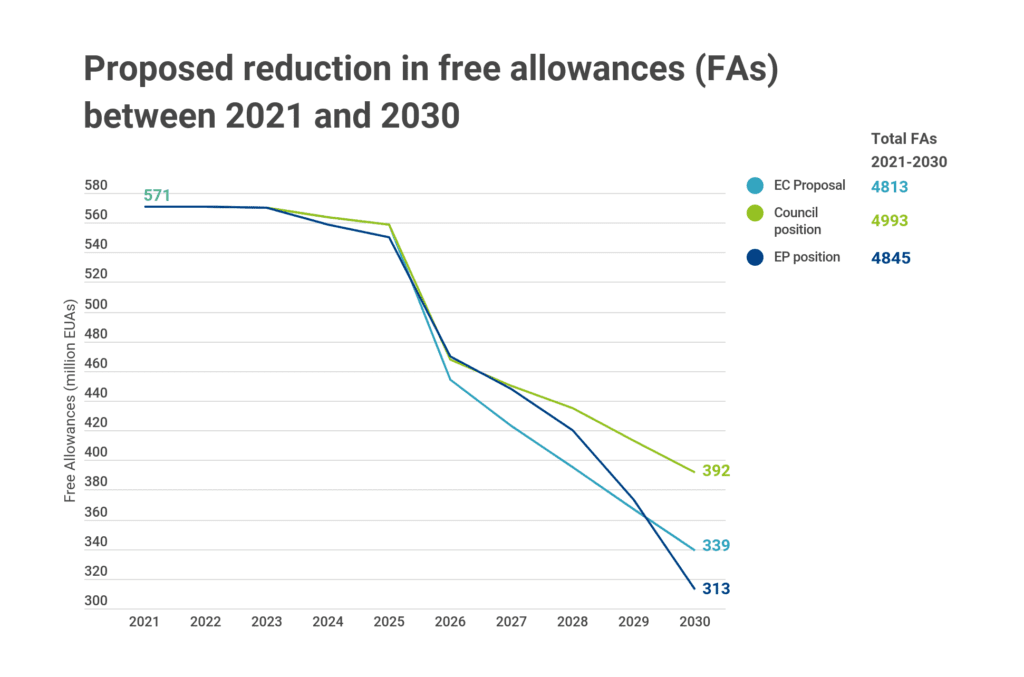

In its proposal, the European Commission envisaged a 10-year transition period for selected sectors to phase out free allowances during which CBAM is phased in. Over this period, the amount of free allowances allocated to these industrial sectors would steadily decrease by 10% each year to reach zero in 2035.

By reducing free allowances to cement, iron, steel, fertilisers and aluminium only by 10% every year, these industries would still receive 50% of the free allowances they currently receive in 2030. Adding these to the allowances allocated for free to all other sectors, the Commission’s proposal still envisages handing out more than 4 billion allowances for free between 2021 and 2030.

In its position, the European Parliament agreed to include more sectors in the CBAM regulation and shorten the free allowances phase-out period to 2032. However, as the parliament wishes to delay the beginning of the phase-out period to 2027, this still leaves half of free allowances to CBAM sectors untouched by 2030. With the inclusion of more sectors in the CBAM, this results in overall in slightly more free pollution permits between 2021 and 2030 than in the Commission’s proposal.

The Environment Council adopted an even more conservative approach that prolongs the availability of free allowances to the sectors included under the CBAM. Under this scheme, these sectors will continue to receive 70% of the current free allowances in 2030. The Council also stretches the phase out of free allowances to 2036.

Innovative solutions

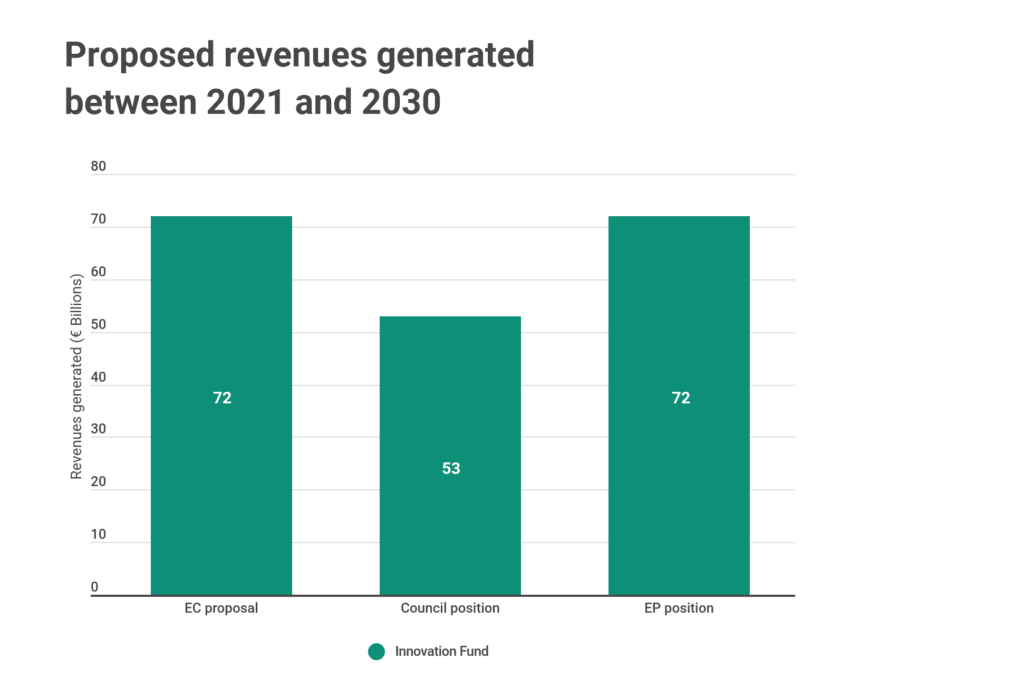

The Innovation Fund was set up to finance innovative projects with a significant potential for slashing industrial emissions, as well as for renewable energy and energy storage.

To incentivise deeper and faster industrial decarbonisation, the European Commission proposed to expand the Innovation Fund by increasing the share of allowances auctioned to finance the fund from all ETS sectors and by diverting to the fund all allowances not allocated for free to sectors covered by the CBAM. This translates to a total of 899 million allowances for the Innovation Fund between 2021 and 2030.

Recognising the importance of innovation to drive industrial transformation, the European Parliament agreed to enlarge the fund, increasing the share of allowances assigned to innovation from auctioned and free allowances as well as adding an additional 0.5% of the total cap to the fund. However, by delaying the implementation of the CBAM and slowing down the phasing out of free allowances to CBAM sectors, the Parliament’s position ends up creating an Innovation Fund comparable to the Commission’s proposal by 2030.

Going in completely the opposite direction, member states agreed to reduce the size of the Innovation Fund. While part of the reduction is due to a proposed redistribution of allowances to the Social Climate Fund, the largest decrease is caused by the slower phase-out of free allowances to sectors covered by the CBAM. As a result, the Innovation Fund would stand to receive only 670 million allowances between 2021 and 2030.

Leaving nobody behind

The Modernisation Fund was established to support 10 lower-income EU member states in their efforts to modernise their power sector and improve energy efficiency. Responding to the need for a faster roll out of renewable energy and higher emissions reduction targets, the European Commission proposed to increase the size of the fund and expand access to a few more member states in need of more support with the decarbonisation of their power sector. In practice, this translates into an additional 2.5% of total EU allowances to be auctioned to the Modernisation Fund and the inclusion of two more member states as beneficiaries: Greece and Portugal.

The European Parliament backed the Commission’s proposal and improved the criteria for assigning funds through this mechanism to ensure the exclusion of funding to fossil fuel projects and to increase transparency and public participation in the project selection process.

The Environment Council also agreed with the extra funds for modernisation but did not back any exclusion of fossil fuel projects nor any extra safeguards on project selection. The only change member states made to the Commission’s proposal was to open access to the fund to more countries compared to the Commission’s proposal.

Making polluters pay their way

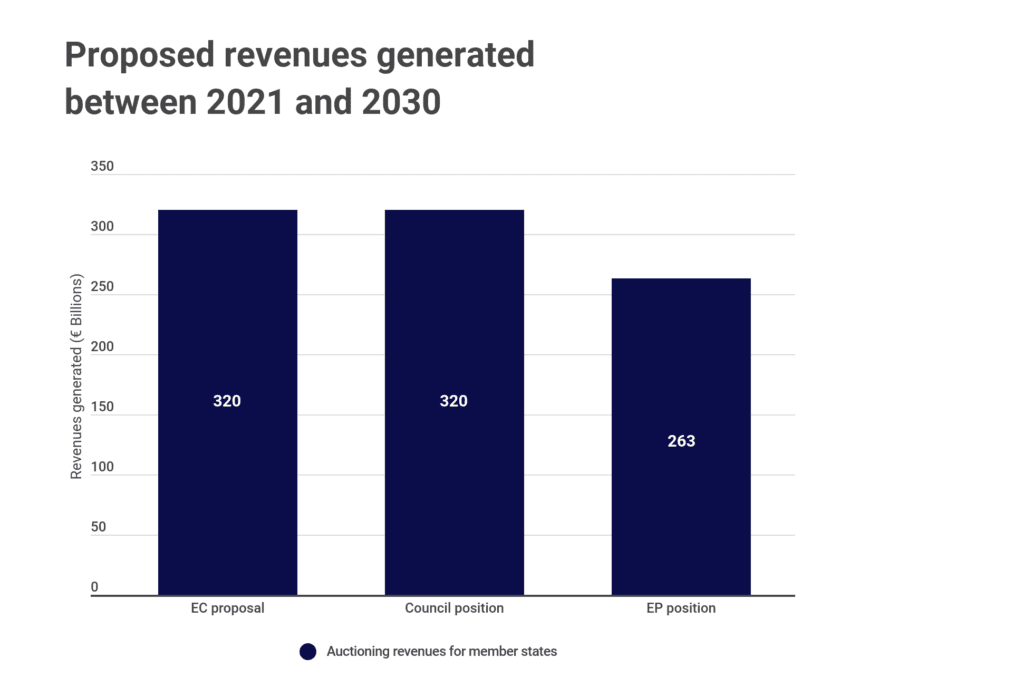

By auctioning EU ETS allowances, member states raise significant revenue from the EU carbon market. This is meant to be reinvested in boosting the green transition and in contributing to achieving EU and national climate targets.

The revision of the EU ETS set out to boost the funds available to member states to invest in climate action, by both increasing revenue flows and making the spending of this revenue on climate mitigation and adaptation mandatory.

As the EU ETS relies on auctioning, reducing the volume of allowances given away for free plays an important role in bolstering the revenue generated by the EU carbon market.

As explained in the section above, by proposing a regular and steady decrease in the supply of free pollution permits starting in 2026 and by including only a handful of sectors in the CBAM, the European Commission’s proposal would yield about €320 billion in auctioning revenue between 2021 and 2030 for all member states (at an assumed CO2 price of €80 per tonne).

In their general approach to the EU ETS, member states maintain the same level of revenue as proposed by the Commission by supporting the same CBAM sectors and start date, as well as by reassigning allowances from the Innovation Fund to the Social Climate Fund.

In contrast, the European Parliament’s position would result in lower ETS revenues for member states. This is due to the fact that the parliament includes more sectors in the CBAM, thereby allocating more auctioning revenue to the Innovation Fund rather than member states’ budgets.

To support national climate action as well as provide more resources to EU funds dedicated to emission reduction and innovation, such as the Innovation Fund, it is crucial that free allowances be phased out as soon as possible, and at the latest before the end of this decade. This would help generate enough resources through auctioning of allowances for member states and for the Innovation Fund, providing incentives for decarbonisation and financial support both at national and European level.

Making the most of the trilogues

After the two co-legislators adopted their positions on the revision of the Emissions Trading System, the three EU institutions will need to hammer out a joint agreement on the central elements of the EU ETS for it to become law.

A first trilogue meeting took place in July 2022 but the bulk of the work is scheduled for the autumn. The coming months will shape one of the cornerstones of EU climate policy.

It is, therefore, essential that policymakers agree the most ambitious deal possible, one that will set the EU on a path to decarbonisation and wean it off its dependence on foreign fossil fuel.

To ensure the bloc reaches climate neutrality by 2050 and fulfils its commitments under the Paris Agreement, it is crucial the three institutions agree on the following elements:

1. At least 64% emissions cuts by 2030

Co-legislators should increase the 2030 ETS target to at least 64%, as proposed by the European Parliament. This should be achieved through a combination of a higher linear reduction factor (LRF) as well as a stronger one-off reduction of the cap, as suggested by the European Commission. The Market Stability Reserve (MSR) should also be strengthened to ensure that allowances are promptly withdrawn from the market as companies reduce their emissions.

2. CBAM in by 2026

Moving away from free allocation of EU ETS allowances and replacing this system with the CBAM is the most effective way of incentivising heavy industry to reduce their emissions.

To this end, CBAM should cover all highly emitting industrial sectors, including hydrogen, organic basic chemicals and polymers, as well as indirect emissions. It should also be implemented as an alternative to existing carbon leakage protection measures as soon as possible, by cutting the share of free ETS allowances for CBAM sectors significantly from 2026 onwards, reaching 0% by 2032 at the latest.

3. Conditional free pollution permits

Sectors continuing to receive allowances for free should fulfil strict conditions and requirements. The allocation of free ETS allowances to industry should be made fully conditional on both energy efficiency audits and the establishment of ambitious decarbonisation plans at installation level. The worst performers should have all their allowances taken away if they fail to fulfil all the requirements.

4. Enough resources for innovation

Reducing emissions and moving to cleaner production processes and fully renewable energy sources is a crucial step to reaching climate neutrality by 2050.

It is, therefore, key to ensure that the Innovation Fund has enough resources to channel into zero-carbon and renewable energy projects as soon as possible.

The Innovation Fund should receive at least 900 million allowances between 2021 and 2030. A faster phase out of free allowances in combination with the implementation of CBAM would free up even more allowances that could be partly channelled to the fund and partly used to finance climate action in member states.

5. Strict Modernisation Fund criteria

The Modernisation Fund is critical for supporting the modernisation and decarbonisation of the power sector in lower-income EU member states. To ensure it is effectively used, the proposed increase of resources to the fund should be maintained and access to it should be made conditional on countries having set a national target of reaching climate neutrality by 2050 at the latest.

Funding for nuclear energy and fossil fuels should be excluded, as it is completely incompatible with the aims of the fund and the overall objective of the European Green Deal.

6. 100% for climate action

The European Commission and the European Parliament are in favour of making it mandatory that 100% of ETS auctioning revenue is used for climate mitigation and adaptation. This position should be reflected in the revised directive. Moreover, it is paramount to provide better guidance and define the list of criteria and activities on which ETS revenues should be spent. While EU member states should be free to decide on what kind of climate action to spend ETS revenues, stricter criteria should be put in place to avoid the misuse of resources to finance unsustainable technologies and practices that are not in line with the goal of reaching climate neutrality by 2050.

To better track how ETS revenues are spent and to compare how member states use this income, it is important to pass the European Parliament’s proposal on stricter and more transparent reporting.